Adani group, an Evil corp?

- Thread starter Pyception

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Kaleen Bhaiya

Innovator

One of the reasons Modi went to USA..I guess we might see some real investigation now. US regulators probe India's Adani Group investor statements -Bloomberg News

He's too important to fail for Modi.

Have some info in the article:It doesn't say which country's residents or investment organisations hold majority of the holdings. Probably USA, UK companies have the most stakes in these companies.

"The FPIs include Societe Generale, Morgan Stanley, General Atlantic, Google and Warburg Pincus. Among the lesser-known FPIs are Albula Investment Fund, Cresta Fund, Moon Capital, ASN Investments, and Ishana Capital Master Fund.

According to the data, it is the lesser-known entities that have their entire India investment in a single group. Five FPIs – ASN Investments, Veda Investors, Deccan Value, A/D Investors Fund and C/D Investors Fund have 100 percent exposure to the GMR group.

Ishana Capital Master Fund, SFSPVI, and Dragsa have 100 percent exposure to the Hinduja group."

Mr.J

Innovator

Secret paper trail reveals hidden Adani investors

Following claims of share price manipulation, new documents uncover potentially controversial shareholders in one of India’s biggest conglomerates

From the outside, the Global Opportunities Fund in Bermuda looked like any regular investment fund: broad, bland, and uncontroversial.

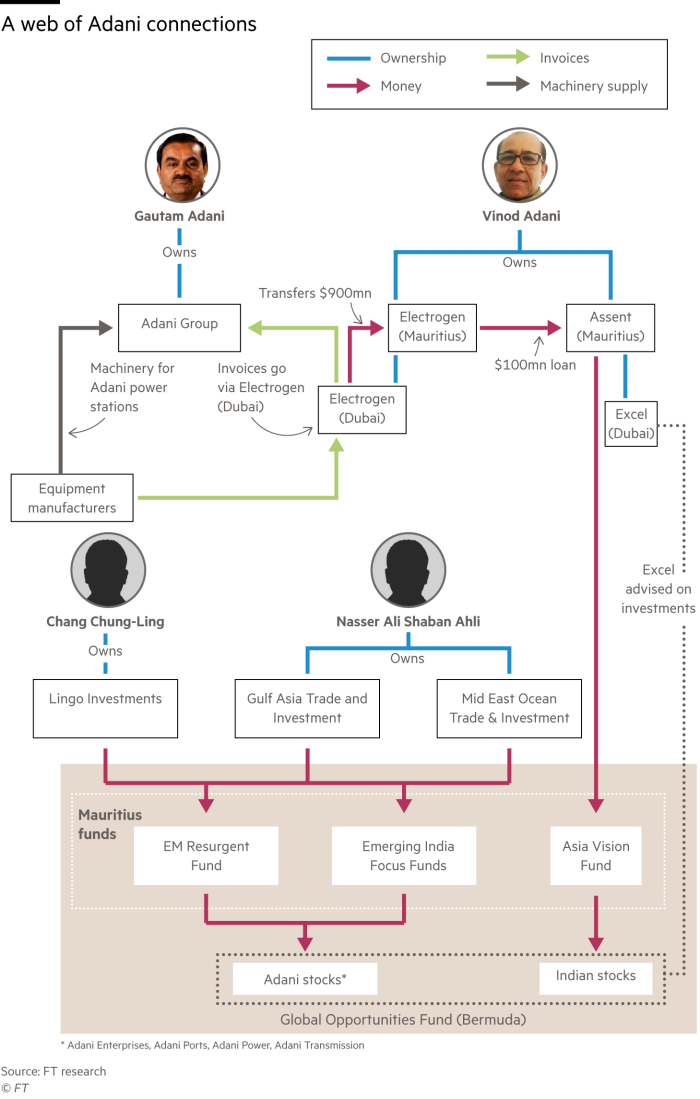

On the inside, however, two men were using the fund for a specific purpose — to amass and trade large positions in shares of the Adani Group, one of the biggest and most politically connected private conglomerates in India.

The two men — Nasser Ali Shaban Ahli from the United Arab Emirates and Chang Chung-Ling from Taiwan — are associates of Vinod Adani, brother of the conglomerate’s founder Gautam. Their investments were overseen by a Vinod Adani employee, raising questions over whether they were front men used to bypass rules for Indian companies that prevent share price manipulation.

The intricate paper trail that shielded their identity from regulators and the public is laid bare in documents shared with the Financial Times by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a network of investigative journalists.

It is the first time that potentially controversial owners of Adani stock have been identified since the American short selling firm Hindenburg Research published an explosive report in January that accused the Adani Group of running the “largest con in corporate history”.

Hindenburg alleged that entities controlled by associates of Vinod Adani manipulated the share prices of some of the group’s 10 listed entities, sparking a furore that has knocked more than $90bn off the conglomerate’s valuation. The allegations in the report were strenuously denied by the group.

In response to questions from the FT, an Adani spokesperson also said its listed entities are in compliance with all laws. Lawyers for the company that set up the investment structure denied there was any wrongdoing associated with it.

The new documents identify Ahli and Chang as two of the most significant investors in the broader scheme outlined by Hindenburg.

They outline a series of bespoke investment structures within the Global Opportunities Fund that were used by Ahli and Chang exclusively to trade Adani stocks.

People familiar with the structures claim parallel sets of books at the fund provider and a Russian doll of companies and funds masked their stakebuilding. “Two sets of accounts were done. One was for regulators. The second set was for each investor mapping their holdings,” says one of the people.

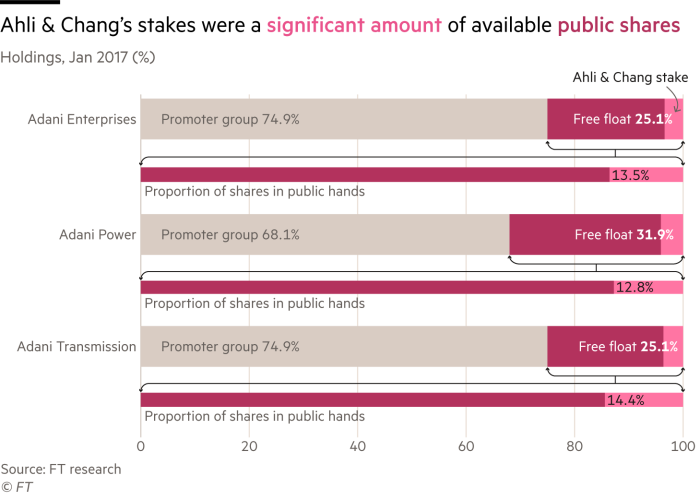

According to the documents, in January 2017 Ahli and Chang secretly controlled at least 13 per cent of the free float — the shares available to be traded by the public — in three of the four Adani companies listed at the time, including the group’s flagship Adani Enterprises.

Their relationship to Vinod Adani matters because he is part of the so-called promoter group, an Indian legal term for corporate insiders whose shareholdings are not supposed to exceed 75 per cent under stock market rules. Breaches of the rule can lead to delisting.

Documents show that Ahli and Chang began their investments in Adani stocks in 2013, when the group sold equity to private investors to increase the public shareholding at its then three listed companies as regulator Sebi, the Securities and Exchange Board of India, sharpened enforcement of the 75 per cent rule.

Were Sebi to treat the two men as proxies for Vinod Adani and so part of the promoter group, it would mean Adani companies repeatedly breached the rules designed to prevent artificial inflation of share prices.

Ketan Dalal, founder of Katalyst Advisors, a Mumbai-based advisory firm, says that “if the free float of a stock was much smaller than visible to the public eye, it allows the price to be manipulated”. Commenting on the rules, without reference to Adani or any other specific company, he says that would be “indirect market manipulation: others see the price go up and could get enticed”.

The new documents include information from police investigations, corporate registries, bank records, stock market data, and correspondence, which the OCCRP has also shared with The Guardian.

They mostly focus on 2012 to 2018, a key period for the Adani Group when it established itself as one of the champions of Indian business. Its interests now range from energy and transport to edible oils, television and sports teams.

Although the Adani Group says it has not been granted favours by the government of Narendra Modi nor any other, its expansion has gathered pace since the prime minister took office, and often dovetailed with the Indian state’s economic agenda.

A package of reforms in 2018 allowed Adani to add six privatised airports to the conglomerate’s strategic interests the following year. It is India’s biggest private thermal power company, biggest private port operator, biggest private airport operator and biggest private coal importer. Gautam Adani has been referred to as “Modi’s Rockefeller”.

Adani strenuously denied Hindenburg’s allegations and responded by calling the report “a calculated attack on India, the independence, integrity, and quality of Indian institutions, and the growth story and ambition of India”.

Hindenburg’s allegations have already spilled into Indian politics after opposition figure Rahul Gandhi raised questions in parliament about Modi’s ties to Gautam Adani. The new documents could broaden the political impact because they show that Indian regulators have long suspected a conspiracy to manipulate Adani shares, contrary to the impression given in an affidavit to the Supreme Court this year, when the regulator said “the allegation that Sebi is investigating Adani since 2016 is factually baseless”.

Two separate investigations into Adani were under way in January 2014, according to previously unreported Indian government correspondence between Sebi and the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, which polices smuggling and economic crime.

The head of the DRI wrote to his counterpart at the regulator because Sebi was investigating “the dealings of the Adani Group of companies in the stock market.” His letter was accompanied by a CD of evidence from a DRI probe into alleged inflated invoices at Adani power projects, and said “there are indications that a part of the siphoned off money may have found its way to stock markets in India as investment and disinvestment in [the] Adani Group.”

The DRI sent demands for information about Adani just before Modi took office in May 2014, after a campaign in which he criss-crossed the country in an Adani jet and helicopters. Three years later the directorate’s adjudicating authority cleared Adani and closed the case.

The documents also raise a broader question about whether international regimes to identify the beneficial owners of assets are fit for purpose.

The investment structures were provided by an Indian financial group now called 360 One. The same firm has previously attracted scrutiny for structuring a Mauritian fund that was used for several years to hide the names of participants in a highly controversial Indian transaction in 2015 involving the fraudulent German company Wirecard.

An Adani spokesperson said its listed entities were in compliance with all laws. “These are nothing but a rehash of unsubstantiated allegations levied in the Hindenburg report,” which she says the group has previously rebutted: “There is neither any truth to nor any basis for making any of the said allegations against the Adani Group and its promoters and we expressly reject all of them in toto.” Adani was not aware of the 2014 DRI documents but added that the Supreme Court had “concluded in our favour” over the matter.

Lawyers for 360 One said the company disagreed with the FT’s version of events, and that no 360 One “entity and/or its employees in their official capacity has been involved in any wrongdoing generally and particularly in connection with the Adani Group”. It also denied any wrongdoing in relation to the Wirecard transactions.

Chang said “I know nothing about this” when asked if he was an Adani associate who secretly purchased shares for them. He declined to say if he knew Vinod Adani, suggested the reporter “might be AI”, and eventually hung up. Vinod Adani and Ahli did not respond to requests for comment. Sebi also did not respond to requests for comment.

India to Dubai, to Mauritius, to Bermuda, Mauritius again, then back to India

The paper trail that links Ahli and Chang to Vinod Adani, and leads them all to a Bermuda fund provided by 360 One, can be traced back to Dubai in July 2009.

Ahli created a company there which, according to DRI documents, almost immediately signed a deal with a Chinese manufacturer of power equipment to supply an Adani project in India, months before the official tender process began.

At the same time Ahli created a Mauritian shell company, whose ownership he transferred to Chang in October 2009.

In early 2010 Vinod Adani took control of both, renaming the Dubai business Electrogen Infra, and its Mauritius parent Electrogen Infra Holdings.

Electrogen Dubai reaped the rewards of acting as a middleman between Adani and its suppliers. The DRI alleged, before its investigation was closed, that while Electrogen was nothing more than a “dummy agent for invoice copying and value inflation”, the profits were real. It found that Electrogen Dubai transferred $900mn up to its parent in Mauritius between 2011 and 2013.

Electrogen Mauritius then lent $100mn to another Vinod Adani company, called Assent Trade & Investment. Vinod Adani signed documents as both the lender and borrower.

Assent used the $100mn to invest in the Indian stock market, by subscribing to shares in the Bermudian Global Opportunities Fund, in 2011 and 2012. Vinod Adani’s money was directed from there into a Mauritian fund called the Asia Vision Fund, which made diversified investments in stocks other than Adani.

According to an agreement signed by Vinod Adani, 360 One paid a Dubai subsidiary of Assent to advise on the investments.

Ahli and Chang reappear in the paper trail in 2013, when Sebi cracked down on excessive promoter holdings at more than 100 companies. Two funds became significant investors in Adani stocks: the Emerging India Focus Funds and the EM Resurgent Fund.

When Sebi inquired in August 2013 about the beneficial owners of the two funds buying large amounts of Adani stock, documents show it was told by 360 One that the end investor was the Global Opportunities Fund in Bermuda, described as a broad-based fund with 195 individual investors.

The two funds favoured an unusual weighting towards Adani: by September 2014, more than a quarter of the Focus Funds’ $742mn in assets, and over half of the Resurgent Fund’s $125mn portfolio, were allocated to three Adani companies, according to documents.

Behind the scenes all but $2mn of $260mn in Adani stock held by the funds on that date were controlled by Ahli and Chang’s companies, documents show.

Like Vinod Adani, they had invested via the Global Opportunities Fund in Bermuda from shell companies. Chang used Lingo Investments, established in the British Virgin Islands in 2010. Ahli used Gulf Asia Trade and Investment in the British Virgin Islands, and Mid East Ocean Trade & Investment in Mauritius, both incorporated in 2011. The source of the money for these three companies’ investments is not known.

Their accounts at the Global Opportunities Fund were overseen by an employee of Excel Investment and Advisory Services, a Vinod Adani company, and Excel was paid an advisory fee related to their investments.

While the Focus Funds and Resurgent Fund were prominent in the names of Adani’s largest public shareholders, the structure allowed Ahli and Chang to buy and sell Adani shares and derivatives in secret. By January 2017 they had accumulated stakes worth $363mn.

‘Longstanding suspicion’

Given that they include new information about previous investigations into the Adani Group, the documents raise new questions about the Indian state and its enforcement of stock market rules on large private companies.

The DRI investigation into Electrogen was set aside by a senior official in 2017, a decision that was appealed internally and eventually endorsed by a tribunal: it found that contracts, which the DRI alleged had earned Vinod Adani profits of at least $900mn when Electrogen acted as a middleman between the Adani Group and its suppliers, were appropriately priced and conducted “at arm’s length”, and that bank records relied on by the DRI were inadmissible as evidence.

A separate probe into an earlier scheme, an alleged circular trade in diamonds by Adani companies to illegally exploit government export incentive schemes, in which DRI documents mention Vinod Adani, Chang and a company represented by Ahli, was also closed without result in 2015. An appeal against that decision was rejected by the Supreme Court the following year.

Aswath Damodaran, who teaches corporate finance and valuation at NYU’s Stern School of Business, says the new information about Sebi’s inquiries from 2014 into Adani nearly a decade ago would likely reinforce questions about the vigilance of India’s regulatory institutions

“The minute Sebi was alerted in 2014, they should have stepped in and acted,” he says. “This is about an institution not enforcing the rules, and the cost of that to the ecosystem.”

Sebi’s chair at the time left in 2017. In March this year he became non-executive chair of New Delhi Television (NDTV), owned by the Adani Group, which said he was an individual of “impeccable integrity”.

Since the publication of the Hindenburg report, close links between the government and Adani, and its closure of probes into the company, have become the subject of much scrutiny.

This year, a Supreme Court-appointed panel of lawyers, former bankers and business executives considered whether Sebi failed to spot possible wrongdoing at Adani.

A May report from the committee that drew extensively on Sebi briefings said the regulator had a “longstanding suspicion . . . that some of the public shareholders are not truly public shareholders and they could be fronts for the promoters of these companies”.

It said those suspicions were “not proved”, and suggested that attempts to do so could be “a journey without a destination” because identifying ultimate beneficial owners behind layers of corporate entities would be “a humongous task.”

Sebi, the May report said, had sought information on 13 offshore entities it considered suspicious from counterparts in jurisdictions including Malta, Curacao, the Virgin Islands, and Bermuda, but had “drawn a blank”.

The regulator submitted its own, delayed report to the Supreme Court on Friday that said its investigation into potential non-compliance with the minimum public shareholding requirements was ongoing, and that identifying controlling shareholders at the 13 offshore entities “remains a challenge”.

Two of the 13 were the funds used by Ahli and Chang for their Adani investments. Adani’s spokesperson said the “provocative timing” of the FT’s story around that event was “to defame, disparage, erode value of and cause loss to the Adani Group and its stakeholders”.

The Hindenburg report also mentioned the two funds in passing, as part of an overall thesis that “Adani’s key ‘public’ investors are secretive and exhibit behaviour inconsistent with normal investment funds”. The report assembled substantial circumstantial evidence to allege that key investors were part of a “vast labyrinth of offshore shell entities” managed by close associates of Vinod Adani.

While Ahli and Chang’s particular interest in Adani has been revealed, it raises questions about the owners of Adani stock inside the other 11 entities, and highlights what one person familiar with the structures described as standard arrangements: “Most Indian offshore structures were designed to bypass the broad-based guidelines.”

From four public companies in 2017, worth $12bn, Adani’s apparent strong stock market following helped it to list two more the following year. After 2020 the valuations of all of them became supercharged, with Adani Enterprises rising 20-fold.

A spokesperson for the group pointed to stock exchange reports on trading patterns in parts of that period submitted to the Supreme Court committee, which said in its May report that they “prima facie, found no evidence of any artificiality to the price rise and did not find material to attribute the rise to any single entity or group of connected entities.”

The conglomerate reached a peak market capitalisation of $288bn late last year. It has since halved.

Secret paper trail reveals hidden Adani investors

Following claims of share price manipulation, new documents uncover potentially controversial shareholders in one of India’s biggest conglomerates

Anti-nationals will say this is an attack on India and ignore blatant corruption cause 'acche din' or something.

cellar_door

Galvanizer

Secret paper trail reveals hidden Adani investors

Following claims of share price manipulation, new documents uncover potentially controversial shareholders in one of India’s biggest conglomerateswww.ft.com

Anti-nationals will say this is an attack on India and ignore blatant corruption cause 'acche din' or something.

I mean, to be fair it is acche din.

For Adani.

Emperor

Juggernaut

Adani ने कांग्रेस शासित राज्यों में कितना पैसा लगाया है? सच हैरान कर देगा

विपक्ष हमला बोलता है, लेकिन उसकी सरकारों को Adani से बिलकुल परहेज नहीं

https://www.thelallantop.com/news/p...nvested-in-rajasthan-west-bengal-chhattisgarhHow much money has Adani invested in Congress-ruled states? Will surprise the truth

Opposition speaks of the attack, but its governments are not at all avoiding Adani

https://www.thelallantop.com/news/p...nvested-in-rajasthan-west-bengal-chhattisgarh

I.N.D.I.A. form for THEIR OWN ACHCHE DIN and few SCHOLARS here on TE & in India thinks that they all (I.N.D.I.A. parties) work hard for people who are experiencing BURE DIN under current Govt.

Gujarat govt paid Rs 3,900 cr of excess payment to Adani Power: Gohil

The Congress leader called it a "textbook case of corruption, money laundering, loot of public money and above all, the classic case of cronyism that the Prime Minister and his government represent,"

The Congress leader called it a "textbook case of corruption, money laundering, loot of public money and above all, the classic case of cronyism that the Prime Minister and his government represent,"

There is stock market manipulation by team Adani, no doubt about it.Anti-nationals will say this is an attack on India and ignore blatant corruption cause 'acche din' or something.

But this is also a political attack. This data is sourced from OCCRP, an actor with a geopolitical agenda.

Here is the list of people who they think is the "Person of the Year" for corruption. I hope you see the pattern.

- 2012 – Ilham Aliyev, President of Azerbaijan – Other mentions: Naser Kelmendi, Milo Đukanović, Vladimir Putin, Miroslav Mišković, Islam Karimov, Darko Šarić[28]

- 2013 – Parliament of Romania – Other mentions: Darko Šarić, Gulnara Karimova[29]

- 2014 – Vladimir Putin, President of the Russian Federation – Other mentions: Viktor Orbán, Milo Đukanović[30]

- 2015 – Milo Đukanović, Prime Minister of Montenegro – Other mentions: First Family of Azerbaijan, Nikola Gruevski[31]

- 2016 – Nicolás Maduro, President of Venezuela – Other mentions: Rodrigo Duterte, Bashar al-Assad, ISIL/ISIS, Raúl Castro/Luis Alberto Rodríguez, Vladimir Putin[27]

- 2017 – Rodrigo Duterte, President of the Philippines – Other mentions: Jacob Zuma, Robert Mugabe[23]

- 2018 – Danske Bank (as Actor of the Year, because it is a company, not a human), for the money laundering scandal[32] – Other mentions: Vladimir Putin, Viktor Orbán, Mohammed bin Salman, Donald Trump

- 2019 – Joseph Muscat, for the flourishing of criminality and corruption under his leadership as Prime Minister of Malta[33] – Other mentions: Donald Trump, Rudy Giuliani, Denis-Christel Sassou Nguesso

- 2020 – Jair Bolsonaro, President of Brazil, for "surrounding himself with corrupt figures, using propaganda to promote his populist agenda, undermining the justice system, and waging a destructive war against the Amazon region that has enriched some of the country’s worst land owners." – Other mentions: President of the United States Donald Trump, President of Turkey Recep Erdoğan, and Ihor Kolomoyskyi[34]

- 2021 – Alexander Lukashenko, President of Belarus, "in recognition of all he has done to advance organized criminal activity and corruption." – Other mentions: Former President of Afghanistan Ashraf Ghani, President of Syria Bashar al-Assad, President of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Former Chancellor of Austria Sebastian Kurz[35]

- 2022 – Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch and mercenary leader, "for his tireless efforts to “extend Russia's vicious and corrupt reach, to steal for Vladimir Putin, and to punish those who resist.”" – Other mentions: European Court of Justice, President of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, President of Nicaragua Daniel Ortega[36]

Sounds like quite true story vro, and not at all linked with opposition.

Mr.J

Innovator

No, I don't. Please spell it out and enlighten us.There is stock market manipulation by team Adani, no doubt about it.

But this is also a political attack. This data is sourced from OCCRP, an actor with a geopolitical agenda.

Here is the list of people who they think is the "Person of the Year" for corruption. I hope you see the pattern.

With the odd exception, these are people who did not align with goals of the US / EU establishment.No, I don't. Please spell it out and enlighten us.

Are they corrupt? yes. Were they targeted solely for that? No.

An organized crime & corruption investigation award that has no mention of people from Pakistan, Mexico, El Salvador. Really?

To put things in context, Joseph Muscat is from Malta, a country of ~500K people, their GDP in 2019 was $15B. Sam Bankman-Fried had a personal net worth north of $20B.

Last edited:

Mr.J

Innovator

OCCRP has extensively covered Pegasus project which is from Israel. Is Israel part of US/EU establishment or not? Or does it depend on which day of week is it?

Pakistan and El Salvador poor economies. Their largest scandals are still a chump change on global scale. Mexico's drug trade have been also covered multiple times by OCCRP.

Sam Bankman-Fried is in prison awaiting trial. Joseph Muscat is a free man and most probably has murdered at least one person.

And GDP means nothing when discussing corruption. Offshore accounts and shell corporations exists. BTW Iceland was a hub of all sorts of corruption leading up to 2008 crisis and its GDP at that time was $21B.

By the way, The page for 2019 person of the year also lists Donald Trump and Rudy Juliani. Is sitting US president not part of the US/EU establishment?

Try harder man. You're two steps away from blaming George Soros.

Tell me you didn't pick up these points from indiaspeaks or some place like that.

Edit: Here's a far simpler explanation for you, OCCRP is mainly filled with journalists from Eastern Europe and Central Asia. That's why their coverage looks like they are part of 'The WEST' while they are just covering what's going on in their countries and their neighboring nations.

Pakistan and El Salvador poor economies. Their largest scandals are still a chump change on global scale. Mexico's drug trade have been also covered multiple times by OCCRP.

Sam Bankman-Fried is in prison awaiting trial. Joseph Muscat is a free man and most probably has murdered at least one person.

And GDP means nothing when discussing corruption. Offshore accounts and shell corporations exists. BTW Iceland was a hub of all sorts of corruption leading up to 2008 crisis and its GDP at that time was $21B.

By the way, The page for 2019 person of the year also lists Donald Trump and Rudy Juliani. Is sitting US president not part of the US/EU establishment?

Try harder man. You're two steps away from blaming George Soros.

Tell me you didn't pick up these points from indiaspeaks or some place like that.

Edit: Here's a far simpler explanation for you, OCCRP is mainly filled with journalists from Eastern Europe and Central Asia. That's why their coverage looks like they are part of 'The WEST' while they are just covering what's going on in their countries and their neighboring nations.

Pegasus project targeted the President and Prime Minister of France, EU officials and diplomats. Benjamin Netanyahu is not particularly liked because of his consolidation of power. A political target is not a country but a particular administration.OCCRP has extensively covered Pegasus project which is from Israel. Is Israel part of US/EU establishment or not? Or does it depend on which day of week is it?

Pakistan and El Salvador have a respective GDP of $376B & $34B. Belarus and Malta have a respective GDP of $80B & $15B. This argument does not hold.Pakistan and El Salvador poor economies. Their largest scandals are still a chump change on global scale.

There are organized crime groups operating across countries with quasi corporate structure in South America. It is ruining the lives of people in Latina America and has created homeless epidemic in US cities. Yet not one of them made it to their Person of the Year list.Mexico's drug trade have been also covered multiple times by OCCRP.

I thought we were discounting corruption in Pakistan and El Salvador because they are small economies, but OK, Joseph Muscat's administration was allowing money from Russia and Middle East to flow into Europe, they were also selling citizenship for money. Corrupt, yes? But hardly worthy of the hall of fame. London today does the exact same job today.Sam Bankman-Fried is in prison awaiting trial. Joseph Muscat is a free man and most probably has murdered at least one person. And GDP means nothing when discussing corruption. Offshore accounts and shell corporations exists.

I pointed out Malta's GDP to paint a comparison of scale, there were far larger corruption issues happening at the time. Sam Bankman-Fried was exposed due to a feud with a rival crypto company, not by investigative journalism.

Donal Trump is many things, most of them not good. But the one thing he is not is a part of the DC swamp. He is hated by US establishment.By the way, The page for 2019 person of the year also lists Donald Trump and Rudy Juliani. Is sitting US president not part of the US/EU establishment?

He was their hall of fame winner, yet the worst corruption charge he had levied against him at the time was paying hush money to a porn star. Most charges against Trump today are for election denial in 2020.

We can discuss issues without resorting to ad-hominem attacks.Try harder man. You're two steps away from blaming George Soros.

Tell me you didn't pick up these points from indiaspeaks or some place like that.

Organizations funding OCCRP, according to their own website -

- U.S. Department of State

- European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights

- United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office

- German Marshall Fund

- Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs of France

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark

- National Endowment for Democracy

- Open Society Foundations

Valid hypothesis. Nicholas Maduro, Rodrigo Duterte were nowhere close to Eastern Europe of Central Asia.Here's a far simpler explanation for you, OCCRP is mainly filled with journalists from Eastern Europe and Central Asia. That's why their coverage looks like they are part of 'The WEST' while they are just covering what's going on in their countries and their neighboring nations.

Political hits do have kernels of truth in them, else they would not be effective, but their use is not to solve the problem but to apply political pressure or bring about a change which is amenable to one's ideology or interest. I am interested in both the interest of the accuser and the actions of the perpetrator because it allows me to make a more informed choice.

EDIT: Fixed typos and added a data point.

Last edited:

Mr.J

Innovator

Pegasus project targeted the President and Prime Minister of France, EU officials and diplomats. Benjamin Netanyahu is not particularly liked because of his consolidation of power. A political target is not a country but a particular administration.

Pakistan and El Salvador have a respective GDP of $376B & $34B. Belarus and Malta have a respective GDP of $80B & $15B. This argument does not hold.

There are organized crime groups operating across countries with qusai corporate structure South America. It is ruining the lives of people in Latina America and has created homeless epidemic in US cities. Yet not one of them made it to their Person of the Year list.

I thought we were discounting corruption in Pakistan and El Salvador because they are small economies, but OK, Joseph Muscat's administration was allowing money from Russia and Middle East to flow into Europe, they were also selling citizenship for money. Corrupt, yes? But hardly worthy of the hall of fame. London today does the exact same job today.

I pointed out Malta's GDP to paint a comparison of scale, there were far larger corruption issues happening at the time. Sam Bankman-Fried was exposed due to a feud with a rival crpto company, not by investigative journalism.

Donal Trump is many things, most of them not good. But the one thing he is not is a part of the DC swamp. He is hated by US establishment.

He was their hall of fame winner, yet the worst corruption charge he had levied against him at the time was paying hush money to a pornstar. Most charges against Trump today are for election denial in 2020.

We can discuss issues without resorting to ad-hominem attacks.

Valid hypothesis. Nicholas Maduro, Rodrigo Duterte were nowhere close to Eastern Europe of Central Asia.

Political hits do have kernels of truth in them, else they would not be effective, but their use is not to solve the problem but to apply political pressure or bring about a change which is amenable to one's ideology or interest. I am interested in both the interest of the accuser and the actions of the perpetrator because it allows me to make a more informed choice.

Ok so you're still harping on about person of the year awards. Have you considered maybe they have awarded person of the year award to someone who's corrupt but not has been in focus as much as they should have been? You have to remember that just a year before Jamal Khashoggi, a journalist, was murdered in Saudi. Joseph Muscat has also murdered a journalist in 2017, Daphne Caruana Galizia, after decades of harassment. In 2019, there were protests going on in Malta against Muscat and his party. Maybe OCCRP chose to give them a boost instead of behing another publication talking about Donald Trump or Rudy Juliani.

Panama Papers and Suisse Secrets were covered by OCCRP. How does not harm 'the western establishment'? Or are we going to pick and choose who is or isn't part of the western establishment? OCCRP, The Guardian, New York Times all have published stories that are against the western establishment and yet our whatsapp graduates call them a part of conspiracy against India or other such nonsense.

both the interest of the accuser and the actions of the perpetrator because it allows me to make a more informed choice.

Interest of the accusers? Have you considered that maybe, just maybe, its just bunch of journalists doing what they can?

If you have documents that will show corruption in Pakistan, Mexico, El Salvador or whichever countries you want them to cover and I'm sure they'll be happy to go through them and publish their findings.

And, 'Donald Trump is an outsider' is such a BS argument put forward by American alt-right and conservatives that I'm not going to bother dignify it with a response.

Vladimir Putin Yevgeny Prigozhin were covered by ORRCP in 2014 and 2022 respectively, the argument that needed more focus respectively in these years doesn't stand scrutiny.Ok so you're still harping on about person of the year awards. Have you considered maybe they have awarded person of the year award to someone who's corrupt but not has been in focus as much as they should have been?

Jair Bolsonaro, Nicolás Maduro, Alexander Lukashenko, Rodrigo Duterte, Viktor Orbán and Mohammed bin Salman are heads of state who are constantly in the public eye, there is plenty of attention and coverage of them.

In an earlier post the argument was that they are objective because of coverage of Donald Trump and Rudy Juliani, this is the diametrically opposite.You have to remember that just a year before Jamal Khashoggi, a journalist, was murdered in Saudi. Joseph Muscat has also murdered a journalist in 2017, Daphne Caruana Galizia, after decades of harassment. In 2019, there were protests going on in Malta against Muscat and his party. Maybe OCCRP chose to give them a boost instead of behing another publication talking about Donald Trump or Rudy Juliani.

Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed in 2017, Muscat was covered in 2019, the year in which he was in a tightly contested race for the position of Head of EU Council. Did he get her killed? Most likely, yes. Was it a political hit? Also, yes. To put things in context, there were many other journalists killed in 2019.

OCCP did not break the Panama Papers story, they collaborated on it. Süddeutsche Zeitung received it from an anonymous source and 40+ organizations collaborated on it, it would have received extensive coverage anyway, by them or somebody else.Panama Papers and Suisse Secrets were covered by OCCRP. How does not harm 'the western establishment'? Or are we going to pick and choose who is or isn't part of the western establishment? OCCRP, The Guardian, New York Times all have published stories that are against the western establishment and yet our whatsapp graduates call them a part of conspiracy against India or other such nonsense.

Again, there is underlying truth to all these stories but they are not purely acts of journalism prioritizing the issues affecting people, but they also have a political purpose.Interest of the accusers? Have you considered that maybe, just maybe, its just bunch of journalists doing what they can?

If you have documents that will show corruption in Pakistan, Mexico, El Salvador or whichever countries you want them to cover and I'm sure they'll be happy to go through them and publish their findings.

Media is not unbaised, either in India or Western countries, it is partisan - pro administration/ideology or pro opposition. I am not discrediting their journalism, but asking people to take their interests also into account. Not understanding interests - geopolitical, political and ideological, leads people to making choices detrimental to themselves. Case in point - Ukraine.

Sure, I understand that position. IMO, Donald Trump is a narcissist with a god complex who's only priority is self aggrandizement. Democracy and its promotion, NATO were the least of his concerns. He worsened US relationship with EU, set in motion the unplanned withdrawal from Afghanistan and was holding foreign policy objectives hostage to domestic politics. So yes, he did not align with the US establishment.And, 'Donald Trump is an outsider' is such a BS argument put forward by American alt-right and conservatives that I'm not going to bother dignify it with a response.

Last edited:

Mr.J

Innovator

When every media is biased then what's point in accusing an outlet of carrying out a political attack? What point does it serve other than diverting attention from the news being reported?Media is not unbaised, either in India or Western countries, it is partisan - pro administration/ideology or pro opposition. I am not discrediting their journalism, but asking people to take their interests also into account. Not understanding interests - geopolitical, political and ideological, leads people to making choices detrimental to themselves. Case in point - Ukraine.

If you're so concerned about biased media then please write about Republic, Zee, and Times of India and the likes. That should keep you busy for days and they pose far greater danger to this country than so called ' political attacks from the west'.

Furthermore, there is a lot of infighting and resentment among the western countries, they're not a monolithic entity. This 'establishment' and 'global elites' and all such terms are just dogwhistles about Jewish people used by American conservaties which has been co-opted by our IT cell members without much thought and blended with our usual persecution complex about being held back from the West.

Now please, if you don't mind, let's go back on topic. Which is Adani and not journalists reporting his shady deals or the West or Ukraine or whatever. Keep the tangents to yourself or start a new topic.

After Adani, OCCRP targets Vedanta; alleges mining giant ran lobbying campaign to weaken green rules - BusinessToday

The George Soros-backed news organisation claimed Vedanta's oil business, Cairn India, also successfully lobbied to have public hearings scrapped for exploratory drilling in oil blocks it won in government auctions.

So, it looks like it's turtles all the way down:

Adani group, an Evil corp?

Getting back on the saddle, in just six months :) https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/adani-in-talks-for-first-major-debt-refinancing-after-hindenburg/articleshow/100965651.cms The effort is a significant test of whether global credit lines will open up to the...

Happy to. If you don't want to bring politics and geopolitics into threads, please refrain from introducing them. Ridiculing and labeling will not help people change their position and only serves to create echo chambers. Fixing problems, like corruption, in our country requires a collaborative effort from voters of both sides of the political isle. The video you posted from the Financial Times highlights it beautifully.Now please, if you don't mind, let's go back on topic. Which is Adani and not journalists reporting his shady deals or the West or Ukraine or whatever. Keep the tangents to yourself or start a new topic.

Anti-nationals will say this is an attack on India and ignore blatant corruption cause 'acche din' or something.

Last edited:

Didn't see any real world implications for the vedanta case. Basically they lobbied by writing letters which is as expected for anyone to do business. Moreover they lobbied citing existing practices by the government in coal mining. Refusing this case then can be blamed as favoring only a few.

After Adani, OCCRP targets Vedanta; alleges mining giant ran lobbying campaign to weaken green rules - BusinessToday

The George Soros-backed news organisation claimed Vedanta's oil business, Cairn India, also successfully lobbied to have public hearings scrapped for exploratory drilling in oil blocks it won in government auctions.www.businesstoday.in

So, it looks like it's turtles all the way down:

Adani group, an Evil corp?

Getting back on the saddle, in just six months :) https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/adani-in-talks-for-first-major-debt-refinancing-after-hindenburg/articleshow/100965651.cms The effort is a significant test of whether global credit lines will open up to the...techenclave.com

Forest and environmental conservation laws have been ignored or changed by the government in a big way. And the general public has only cheered that. Public opinion is largely against the likes of Jairam Ramesh.